Andrew talks about his time in the RAF, which he joined in 1976 as a direct entry weapons technician aiming to become a pilot. He was commissioned as aircrew but left after training. After a short break he had a long career in the RAF, including time at Neatishead, where he was instrumental in setting up and running the Museum.

The Merchant Navy and joining the RAF

I was one of the people caught up in the changeover from grammar schools to comprehensive schools in the late 1970s. I went from an all-boys grammar school to a mixed sixth form college. I didn’t enjoy it at all, so I left before I finished my A-Levels.

I got a job in the Merchant Navy as a Navigating Officer Cadet working for BP tankers. I played a lot of sport and there’s not much you can do in that line on a tanker at sea for six months at a time, so it was a pretty lonely life.

One day, we were anchored off the Norfolk coast and two Lightnings came screaming over the top of the ship. I thought it looked fun, I wanted to do that. The careers information office in Middlesborough told me that my five O-levels were good enough, but most pilots have degrees. The best thing would be to join up as an airman and work my way up from the inside. I joined as a direct entry weapons technician, which involved a 12 month course down at RAF Halton in Buckinghamshire.

In November 1976 I went to RAF Swinderby for my six weeks of induction (also known as square bashing). I then went down to RAF Halton for my year of trade training and learnt all about things that went bang and crash. We also worked on a Vulcan 7 store carrier which carried the 21x 1000lb bombs, as used in Operation Blackbuck.

Lightnings at RAF Binbrook

After finishing my trade training I went to RAF Binbrook in Lincolnshire. This was the only base at the time that had the Lightning fighter jets I had seen flying over the tanker; the only British produced Mach-two interceptor ever. If it was still flying now, it would outperform quite a few of the modern-day fighter jets purely in speed and climbing terms.

My new boss was Flight Lieutenant Peter Plume, who would have to write a report on me when I applied to be commissioned as aircrew. So I knuckled down and worked on the Lightnings. I had some quite good fun really, working on ejection seats and 30mm Aden Cannons, putting them in aircraft and servicing them. This was a stop on the way. After a year Peter Plume said he was entirely happy for me to apply for my commission.

Pilot officer

It took until early 1979 for me to get the blue letter saying I’d been successful at the Officer and Aircrew Selection Centre at Biggin Hill and was now going off to the Officer Cadet Training Unit at RAF Henlow, one of the two places where officers were trained at the time. The other was the famous Royal Air Force College at RAF Cranwell.

I graduated on the penultimate course at Henlow as a Pilot Officer in November 1979. After that all officer training moved to Cranwell. I got time taken off for good behaviour or experience due to having been an airman, so started as a substantive Pilot Officer. Then after being a Flying Officer I was automatically promoted to Flight Lieutenant. After that promotion depends on passing examinations and attending courses and getting the right recommendations on your annual report.

Flying Selection Squadron

Because the failure rate of flying training was so high the Air Force initiated the Flying Selection Squadron. The instructors were volunteer reservists and most of them had been Spitfire pilots in World War II. We did 14 hours in Chipmunks. After your first hour as a passenger, you’d learn how to climb at specific speeds, fly straighten level, and rudimentary aerobatics like a barrel roll. Then you were sent back to Biggin Hill to be reselected, or you carried on to the next course. Luckily for me, I moved onto the next course.

Holding postings in Gütersloh

I went out to RAF Gütersloh in Germany on a holding posting. First I was with 3 Sqn, a Harrier squadron, whilst I was waiting for a place on the next flying course. You saw how the bigger Air Force and the flying squadrons work. I went flying in the back of one of their trainer aircraft a few times, and it was gut wrenching and eye opening to fly over the North German plain in the back of a Harrier, avoiding the American F-15s. They were eager to expose you to this because you were going onto flying training.

From there I was moved across to 18 Helicopter Squadron, run by Wing Commander AFC (Sandy) Hunter, AFC who was renowned for having a fast and fierce temper. However, both the Squadron Leaders who worked for him went on to become starred officers. I did get some flying experience in the Wessex helicopter with them and often flew with ‘The Boss’ himself.

Leaving the Air Force

I’d had a problem with my back for quite a while, and had an operation in RAF Nocton Hall in Lincolnshire, an archaic ex-World War II hospital. I didn’t get back to training until October 1981 and got about 100 hours in on the jet provost at Linton on Ouse before I was ‘chopped’.

Unfortunately if I had to fly the aeroplane, navigate it and fight it, I would be overloaded and make a smoky hole in the ground somewhere. So that was the end of my stab at flying. I drew a line through it and left the Air Force.

So there I was, 26 years old and with no idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

Police Force

Against everyone’s advice, I joined the Police Force. I had naively assumed it would be like the Air Force, full of one for all, all for one, look after your mates and get the job done. Instead, there were a whole bunch of people who were only ever going to be police constables and who took a dim view of anyone who had aspirations to rise through the ranks..

I did the miners’ strike where police were brought in from all over the country, which was not particularly nice to see. There’s a lot said about Orgreave Coking Works, but it’s all from the perspective of the poor old coal miners. They’re out on strike, they’ve got no food, and the nasty fascist policemen are beating them up. But some of the things I saw that day were anarchy. There were apples and potatoes with razor blades and 6in nails in them being thrown under horses’ hooves, and plastic bags with paint stripper being thrown at us policemen. That’s the day Arthur Scargill laughingly said he’d been assaulted but no-one assaulted him, certainly not the 300 policemen surrounding him.

So, after two years, I decided the Police Force wasn’t really for me.

Rejoining the Air Force

It was a long shot, but I wrote to the Air Force asking if I could come back. I passed the aptitude tests for a fighter controller and re-entered the Air Force in October 1984. I took a four weeks refresher (SERE) for people like me who were returning to the Air Force. It was also a course for specialist pre-qualified doctors, dentists and nurses.

We had to have injections and inoculations, in case we had to go to exotic places at short notice. At the medical centre they got the doctors and nurses to do it themselves. You should have seen the doctors trying to inject people! In the end one of the nurses said, ‘Just go and line up over there, I’ll do it.’ It was a great laugh.

Fighter Control training

After a holding posting at High Wycombe for a few months, I started my fighter control training at RAF West Drayton. The officers’ mess was a six-story building in a built-up area of London. All the other messes I’d stayed in had been built in the 1930s and were in the middle of nowhere.

The Fighter Control Branch is responsible for the defence of the UK homeland from air threats. All aircraft flying into the UK have flight plans so you are expecting them, and you’re looking for the things that aren’t flight planned. There’s the part when you send fighters out to intercept incoming aircraft, which is the Intercept Controller’s job. The Systems Officer produces the Recognised Air Picture (RAP). This shows the position and identity on a radar screen of all the aircraft in a specific area of responsibility. They also integrate the radar and the comms into the system and produce the display for the Intercept Controllers to do their part of the job.

Immediately prior to qualifying as a Systems Officer I went to Neatishead to do some practical training. I loved it there. It was quintessentially English and Norfolk had a slow pace of life. Horning had one pub, a shop, a few houses. Even Wroxham was almost village like at that point, the only shop in town was Roys of Wroxham and a couple of pubs and a hotel. The people at Neatishead were okay too. We were outsiders looking in at that stage though, as five or six of us were there on a course with an instructor.

IDRO, TPO and QRA

After qualifying I went on to RAF Boulmer in Northumberland, I was initially an Identification and Recognition Officer (IDRO), which was the first level of operational role on the systems side of the house. I was selected relatively quickly to be trained as a Track Production Officer (TPO). This is the role that supervises the integration of the radar, information from ships, the airborne early warning aircraft (AEW) , the comms, the radar feeds, that collectively make up the Recognised Air Picture.

There were two types of working. One was days, where people would come in at 8am and finish at 5pm; the other was evenings when you would come in at 5pm and finish whenever the night flying finished.

Running concurrently with them was the people working Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) shifts. Two airfields in the UK, one in the north and one in the south, would have aircraft carrying live armed missiles. If the IDRO saw something suspicious, they’d set in motion a system to scramble those aircraft to intercept and identify the unknown aircraft. On Q-nights and Q-days shifts, you’d work in a two day, two night, four off cycle. With Q-days, you’d come in at 8am and work until 5pm, whilst Q-nights were 5pm until 8am.

Cyprus

In April 1986 the Americans bombed Libya in Operation El Dorado Canyon. It was decided that there was a credible threat to Cyprus, as it was the closest British base to Libya and the Americans had been allowed to use bases in Britain to fly to Libya. In Cyprus at the time 5 Sqn (Lightnings) were undertaking their annual armament practice camp (APC).

I’d just finished a Q-day shift at 5pm and caught the bus home to Horsham St Faith where I lived in married quarters. Around 7pm, my wife had just put dinner on the table, the telephone rang. It was Dieter Dreyer, the German exchange officer at Neatishead. My wife answered the phone and tried to make small talk with Dieter – as was usual; unusually he was very abrupt and said ‘I need to talk to Andy right now’! I picked the phone up, and Dieter said, ‘Right, in an hour there will be a bus to collect you. Pack your kit, you’re going to Cyprus.’

It was odd in itself for an exchange officer to give an order like this, but what made it more abnormal was that to be able to travel, I had to have a NATO travel order. That’s like a passport for NATO countries and other countries around the world that certifies me as a British officer travelling on Government Business. Because Dieter was the duty Master Controller then he had to authorise and sign my NATO Travel Order. So you’ve got this British officer being sent off to Cyprus with a German officer’s signature on the paperwork – bizarre!

As I was saying goodbye to my wife, our golden labrador Sam ran through the open front door and jumped on the bus. He wouldn’t get off it, I had to carry him back into the house.

There were seven or eight of us and we ended up at RAF Binbrook in Lincolnshire. We were packed in the back of a Hercules with live red top missiles. The French wouldn’t let us overfly France so we had to go all the way down the French coast, turn left through the Bay of Biscay, past Gibraltar, flying past the ships of the American sixth fleet which were in the Mediterranean at the time and, understandably, trigger-happy.

We made it to Cyprus and went to reinforce the radar station at Mount Olympus. It was a small unit called 280 Signals Unit, which supported the APC aircraft at the Akrotiri airfield. I was there for around six or seven weeks. The unit closed down in 1994.

in the centre of the picture is covered in ice about 2in thick.

Back to Neatishead

I was posted back to Neatishead as a TPO working in the ops room. There were a really good bunch of people there, with a few notable exceptions.

One great character at Neatishead was a guy called Winston Pewsey. He was of Caribbean descent, an absolutely lovely man. He was married to a nurse in the Norwich and Norfolk hospital. The ops room at Neatishead was in the dark, it was three tiers and the systems area was at the very front in the bottom. After two hours in the ops room you’d be relieved and could wander around. Winston would come in and stand at the top of the stairs and shout ‘Hey, where are ya, I can’t see ya?’ A fantastic bloke with a great sense of humour.

Don Reed

Don Reed was the Station Commander at Neatishead after Joan Hopkins. As far as I’m aware he was the first ever navigator to become the boss of a fighter squadron (43 Sqn I think). – in those days it was normally a role reserved for a pilot. Anyway, he was the Station Commander at Neatishead on my first posting there. He was very popular with us.

The time came that our Sqn Cdr (Tony Vass) was moving on to his next posting. When people left their posting, there’d be a formal dinner to dine them out of their current job and the station and on to the next. It’s pre-dinner drinks, and a formal dinner, and then things tend to get rowdy after a while.

A number of exchange officers were entitled to tax-free status and got a load of tax-free hooch, and there was a party circuit run by them. But there was one exchange officer who was an American Southern Baptist, a very straight-laced man who’d cycle from Horsham St Faith (Norwich) to Horning and back every working day! He didn’t drink alcohol, didn’t swear. Some fool had made him President of the Mess Committee (PMC), which meant he was in charge of the mess and he could issue punishments as he saw fit.

We decided to make Tony Vass’ dining out memorable. There were signs secreted on the wall behind the top table, one of which said clap and the other which said a word similar to clap but with the second letter changed to an r. There were explosives, alcohol was drunk, things went down, and it was a great night.

On Monday morning I and two other colleagues (‘Gorky’ Park and ‘Chunder’ Hughes) were called in to see the Major. He was known as a ‘hats on’. Not offered a seat, stand to attention,, keep your hat on, huge strips torn off you, punishment issued, get out of his office. He said to each of us, ‘I want a 3,000 word service paper on my desk next week on the physiological effect of alcohol on the human body.’

The Major’s office was in the radar building, about 200yd from the ops building. On the way back Don Reed’s staff car pulled up next to us. He wound down the window and obviously saw three dejected junior officers. We told him we had just been to see the PMC who wasn’t too pleased with us. He told us to report to his office in Station HQ in ten minutes – ‘great’ we thought – ‘yet another bollocking’! We got there and were sent into his office by his PA; we stood to attention and saluted, after which Don Reed told us to take a seat and take our hats off. He told us ‘Absolutely cracking night Friday lads, thank you very much’. Don’t you worry, I’ve squared away the PMC and told him not only what’s expected of you as junior officers, but what’s expected of him as the PMC.’ He was so cool, calm and collected about it. It could have been a big black mark on our careers but he just went: ‘you work hard and you play hard’ in this man’s Air Force!.

That was an ethos I carried throughout my career. Fifteen hours sitting and watching a radar screen was hard and tiring. And if nothing is happening for long periods of time you can get dispirited. It was 95% boredom and 5% absolute panic, and you’d have to go from boredom to panic in a split second. The things you’re dealing with are going 500-600mph, so you’ve got to be instantly alert and on the ball. So, we did work hard and we did play hard. We drank lots of beer, and if we did any damage we paid the bill. Throughout most of my career it was like that, and I realised at the point it stopped being like that it was probably time for me to retire.

Instructor at the School of Fighter Controller Detachment

I was selected to be an instructor at the School of Fighter Controller Detachment. At that point the school was split between West Drayton, which was planning to be closed, and Boulmer where the full school subsequently relocated to. I was posted to Boulmer. In our office there were around eight instructors, and you tended to form a close bond with the people you worked with every day. So we were a close knit group of friends. Without exception every instructor I worked with’s sole aim in life was to get people through the course and qualified.

Myself and a guy who went by the nickname of Dog’s Breath used to get the really difficult students, those who were hanging on by their fingernails. We might have used unorthodox tactics but we got them through. I used to have an 18in ruler sellotaped to one of those plastic knives you get in canteens. If my student wasn’t doing particularly well in the ops room, I’d poke him with it. It was a light-hearted way to divert their attention from how badly they were doing so you could get an input into them they’d be receptive to.

You had to go on an instructional techniques course at RAF Newton, from where you’d normally qualify with a B-1 or B-2 grade. After a period of time I became an A-1 instructor, which was quite a feather in my cap.

Again we had a good bunch of people, a good boss (Des Allen), and we worked hard and played hard, often with the Boss leading from the front!

Commander of mobile radar convoy

From the School I moved just up the road to become the Commander of a mobile radar convoy located seven or eight miles away at a former World War II airfield, Brunton. The radar was on the spine of a lorry which would tilt up and was out in all the elements.

This was a leadership challenge. I was responsible for a hundred men, from the lowest rank of airmen to the highest rank Warrant Officers, engineers. And I was the boss of an Engineering Officer who was a Flight Lieutenant just like me.

I was there until 1992. Although I made good friends I was glad for it to come to an end and wanted to move onto something different.

Waddington or Cyprus?

The RAF had scrapped the Nimrod AEW programme and instead purchased seven Boeing 707 AEW aircraft from the Americans – subsequently named the E3D. They were to be based at RAF Waddington and I’d been selected to be one of the first crew – I saw it as a way to get me flying again.

In the Air Force you normally never stay anywhere for more than three years, you’re posted around constantly. My Posting Officer was an Irishman called Paddy. He too was moving to a new job and so we had invited him to RAF Boulmer to be ‘Dined Out’. I was standing at the bar with him at about 2am on the Saturday, and he said ‘So you’re off to the E-3 then. How do you fancy going to Cyprus instead?’ I got home at about 3am, slightly the worse for wear, woke my wife and said, ‘How do you fancy living in Cyprus for a couple of years?’ She obviously preferred Cyprus to Lincoln so it was a case of ‘all change’!

By this time we had two young children and we thought what a fantastic two or three years it would be for the boys to grow up in Cyprus. There were no married quarters so instead you got ‘hirings’. The Air Force would hire houses off local people, and you’d pay the Air Force the rent. I ended up in a beautiful three bedroom villa. The carport was about 60ft long, covered in grapevine, and the gardens were about an acre with peach trees, plum trees, olive trees, you name it. The owner came up once a week to look after his fruit trees because they were highly prized in Cyprus. So, we got to know him, he was a lovely guy.

In Cyprus I’d become the Training Officer after a while so it would use my experience from the fighter controller school but initially I worked Q-shifts up at Troodos, the mountain range of which Mount Olympus was the highest peak. The radar was 6,000ft up on Mount Olympus. 280 Signals Unit was the radar unit, RAF Akrotiri was the airfield, and then the sovereign base area was down on the coast.

The QRA shifts were the same as they’d been at Neatishead, but for those working days, the only day you worked a full 8am-5pm was Monday. Every other day, Tuesday to Friday, you worked 7am-1pm and finished. I suppose that was to fit in with what the rest of the island was doing with a siesta in the afternoon.

You could go snow-skiing in the morning and then go down the mountain to the beach and be water skiing in the afternoon. We got a lot of snow. The radar site was surrounded by a 12ft barbed wire fence, and we used to get 12-14ft of snow which would blow in. People used to ski over the top of the fence and over the radar site. The snow up there was so bad that in October we’d have to get out the snow tunnels. Imagine a u-shaped corrugated iron air raid shelter on wheels on a little railway track. We’d join them together on their tracks so you could walk around the site once the snow came. In the spring, it wasn’t uncommon for two or three cars that had been snowed in to slowly emerge out of the snowdrifts as the snow melted. It was an incredible place.

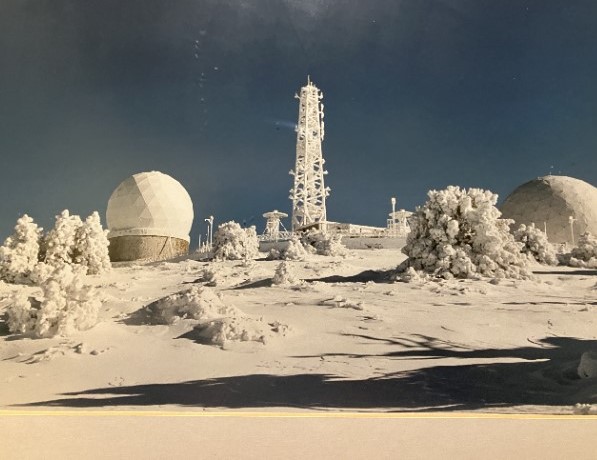

Olympus Radar; 280SU; RAF Troodos in the Winter, 6,000 ft up a Cypriot Mountain. The aerial

in the centre of the picture is covered in ice about 2in thick.

I’d been there for about 18 months when there was a round of defence cuts. The Commanding Officer of British Forces Cyprus at the time was none other than Air Vice Marshal AFC Hunter, AFC, who I’d known at Gütersloh all those years before. History had it he was told he had to save £19,000,000 a year from his budget and they found in the books that 280 Signals Unit cost around that much. So that was what was closed in May 1994.

It was a short-sighted decision because we did more than just armament practice camps. Our radar could see into Israel and Syria. We worked with the Americans who had a specialist aircraft based out there which was a modernised version of the one Gary Powers was shot down in over Russia in the 1960s. So we used to do a lot of what can be loosely termed ’intelligence gathering’.

Shortly after the decision to close it was made, a two star Army Officer (Alex Harley) took over as the Commanding Officer of British Forces Cyprus. They alternate the top job between Army and RAF. When a unit is closed down there is a formal parade and this Army Officer came up as reviewing officer. In his speech he said if he had been the Commanding Officer of British Forces Cyprus when the decision was made 280 SU would not be closing down.

But the die was already cast, people were posted out. I stayed back with Sqn Ldr Taff Curtis (280 SU Commanding Officer) , who I’d known at Neatishead, to help him close the unit down. The radar was a massive Type-84 radar. The easiest way to get rid of it was to get a Greek scrap metal merchant to come and cut it up, pay the Air Force for the scrap metal, and drive it away on his lorries. Four days after the guy had started cutting the radar up the intelligence people at Episkopi rang and said ‘We’ve got a task for you.’ I said, ‘Forget it. The radar is just going out the gate on the back of a Greek scrap lorry.’

So that cut short my three years in Cyprus at just under the two year point. The irony of the situation was that the Air Force had to reopen the place in a smaller fashion further down the line, so there’s still a radar up at the top of Troodos with an RAF presence.

Sector Operations Centre at Neatishead and ops room Master Controller

We drove back home from Cyprus, through Europe to Neatishead. The SOC at Neatishead was moving to High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, Headquarters 11 route. So my job was packing up books, burning classified documents, and all the rest of it.

I then had to go back into the Ops Room and requalify, as in the time I’d been out of the mainstream a whole new computerised system had come in. It was called the Improved United Kingdom Air Defence Ground Environment (IUKADGE) and had effectively taken the whole system 20 years into the future. I went in as a Senior Flight Lieutenant to do my IDRO and TPO qualifications again.

After requalifying I was selected to become a Master Controller and ran the ops room.. By this stage, I’d built up a good wealth of knowledge and I understood how all the bits of the jigsaw fit together, as the systems side had to integrate everything and make sure it all worked. So that was a fantastic job. I was also made Deputy Squadron Commander. That was in early 1997.

Neatishead Museum

The Neatishead museum was started by an officer who had sold the idea to the head of the Air Force at the time. He’d assembled a team of volunteers and been full steam ahead in doing it. He was promoted and moved on and I was asked by my boss to take over as the officer in charge of the museum as my secondary duty.

There’s a room in the Museum called the Hobley room which is where the telephone exchange used to be. My wife and I painted all the walls dark green because it was the only free paint we could get. I built the room dividers and we got sponsorship from a local firm. I got the original heraldic crests, took them to a place in Norwich to frame them. Half way through the framers went bankrupt and the liquidators wouldn’t return the remainder. Eventually we got them back, got the rest of them framed, and we mounted them on the walls – crests from various squadrons and stations who had ever had anything to do with Air Defence.

It became pretty clear to me that the museum could really go somewhere, but it needed to be put on a proper footing. It wasn’t a secondary duty, which is something an officer is supposed to spend three or four hours a week running. I talked to the Station Commander (Gp Capt Barry Titchen) and he found a bit of money from his budget and we were able to install a museum curator, the recently retired Warrant Officer at Neatishead, Dougie Robb. He worked two or three days a week there, answering the phone, organising open days and tours.

By the time I left Neatishead on promotion at the end of 1997, the museum was pretty well set up. Volunteers would come in and run the cafeteria, they’d work the exhibits, and conduct tours. It was the beginnings of the museum you see now. A few of the volunteers were ex-RAF, there were one or two that had been national servicemen. One had been the BT technician at Neatishead, since, though RAF has its own communications people, the telephone system was looked after by BT.

One of the volunteers was the recently retired Sqn Ldr Ops called Roy Bullers who had been in the Air Force during World War II. If you have a vision in your mind of an RAF officer, it would be him. He had a big white handlebar moustache.

Roy and his wife, Sheila, lived in a beautiful old thatched cottage in Hoveton with a garden that stretched out down to Hoveton Broad. He would do things like invite six or seven of the junior officers with their wives to his house on a Saturday afternoon to play croquet. It would be like a bygone era, playing croquet on his beautifully manicured lawn that sloped down to the Broad, drinking Pimm’s, the ladies in their flowing frocks and big sun hats.

Roy used to ride a moped from Neatishead to his home in the Broads wearing a bright yellow oilskin suit and a crash helmet with it. I mention Tony Vass’ Dining Out Night earlier and of course Roy attended. Unusually for him, he’d had a few beers and at around 11pm he left for the night. An hour later he walked back into the mess with bits of branch and leaves stuck in his hair. He’d obviously had one too many, crashed his moped into a hedge and decided to get the bus home later. But I never saw him like that again.

When he retired, he was at the museum pretty much five days a week. One of life’s lovely men with a wicked sense of humour. He was sorely missed by everybody when he died a few years ago.

In the January 1997 New Year’s Honours List, I got an Air Officer Commander in Chief (AOCinC) commendation for the work I’d done on the museum.

SHAPE

Then I was promoted to Sqn Ldr and posted to SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers in Europe) in Mons in Belgium.

It’s a multinational environment, so all the NATO nations are represented. I was put onto the NATO ACCS (Air Command and Control System) programme. As I said earlier, between me going to Cyprus and coming back the UK we had installed IUKADGE which had catapulted the UK Air Defence system 20 years into the future. NATO was trying to do the same thing, and at that time the UK were part of the NATO ACCs programme which was all about computerising NATO’s air defence and air operations in the way that IUKADGE had for the UK. I stayed at SHAPE for three and a half years which is longer than normal. I had done a lot of work on the programme that was allegedly coming to fruition (at the time of writing this in June 2024 it still hasn’t!!!) so it made sense for me to stay there rather than someone new have to learn the ropes. I made some very good friends there. It was less of the play hard because that tended to be British and maybe German way of life, not NATO-wide. It was effectively an eight till five way of life.

I did quite a bit of travelling, particularly around Turkey, Greece, Germany and the Netherlands to do with a project I was working on. There was nowhere near so much pressure, just long hard days writing and researching standards and so on.

School of Fighter Control, Boulmer

In June 2001 I came home and went to the School of Fighter Control which by this time was entirely installed at RAF Boulmer in Northumberland. The school had three squadrons: the Ab Initio training squadron which took people like I had been at West Drayton many years previously, trained them and pushed them out to the other side. There was the Postgraduate Squadron who ran lots of courses that you had to do before you could move up in job level as I had gone from IDO to TPO. Data links courses, inset courses, TPO courses…

I was the boss of the Standards Squadron, responsible for the standard of the training and the output across all of the courses and anything that did not clearly fall under the remit of the other two squadrons! In that job you deputised for the Wing Commander, so you were also Deputy OC of the School. It was quite a challenging job. At its busiest we had 98 courses on the books that could be called on. I had a team of about six junior officers and three or four civilians who ran the registry and the office that did all the scheduling. I was there for two and half years, thoroughly enjoyed it.

When my boss decided to leave the Service at short notice, I was given the paid rank of Wing Commander. So, I was paid as a Wing Commander but still a Squadron Leader running the school.

There was one event that stands out in my mind. The ‘powers that be’ decided that the E3D AEW aircraft should be manned by aircrew and that they should get rid of these fighter control guys down in the back end – after all – what do they know about flying? Well, my question was ‘what do the air crew know about fighter controlling’? We were sent three navigators who had been withdrawn from flying duties and told that ‘they would qualify as intercept controllers’. I was really quite wary about this. You had to have an aptitude to do the job, think in three dimensions and all the rest of it. That’s clearly why they thought these navigators would do well, but let’s not forget that they had already been withdrawn from flying duties! One was a female who was an ex-Hercules navigator, one a Tornado F3 navigator and one an ex F4 navigator. Although we joke about it, it’s a serious bloody business and there is potential to cause mayhem – if you get it wrong it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that you are going to send an F3 Tornado through the side of a 737, an air to air collision. It became rapidly apparent that we were expected to run these people through an Ad Hoc course, qualify them and send them off to Waddington to go in the back of the E-3.

GASOs (Group Staff Orders) are edicts that tell you what you have to do and how you have to do it. I got my head into the books, and I saw that what we were doing could have legal ramifications. I pushed back against 11 Group saying it was not legal, it was potentially dangerous and not an approved course in the legal sense of the word. Luckily enough I managed to get my station commander, the group captain of Boulmer, onside. Despite my reservations we were still trying to get the job done so I had the best instructors for these people. Two of the three failed very early on and one, the ex F3 navigator, complained about the standard of instruction he’d had. As OC of the School It was my turn to conduct a ‘hats on’ interview. When he came into my office he started off with his excuses and complaints; I listened for about 30 seconds and then said, ‘This is a monologue, not a dialogue; clearly you are not the sharpest knife in the Navigator drawer, I’m very sorry you didn’t make the standard. Goodbye.’ We documented it absolutely precisely because there were going to be ramifications.

The girl who was the Hercules navigator didn’t last as long as this guy did. Your brain is wired in that way or it’s not and she was overwhelmed. The one guy that kept his head down, really worked hard and would have just about passed the course at the end of the day, learned that he had been promoted to Squadron Leader on the day before he was due to undertake his final checks and he was posted off somewhere else. So, that whole probably six month period of frenetic activity, making myself extremely unpopular with the wheels at 11 Group need never have happened. But it did reinforce in a lot of people’s minds that we’re not playing at this, it’s a serious bloody business. The potential if you get this wrong is massive.

Time at the Ministry of Defence

In 2004 I went to work in the dreaded Ministry of Defence (MOD) building and I hated it. I had a flat in Canary Wharf paid for by the Air Force, but it was London, the big city. I would go into work at eight o’clock in the morning at leave at seven o’clock at night and come into work the next morning at eight o’clock without speaking a word to anyone. I found it a soulless place with too many people and not enough trees.

Although I was told that the MOD tour was the one I needed to do to get myself fit for promotion to Wing Commander I got out early as part of a process known as rustication which was to move people out of London. My family were still up north, my children at school in Barnard Castle. I told the postings officer that happiness to me is far, far more important than promotion. So I managed to swing the job to go to Boulmer, still working for 11 Group so still recognised as a staff work job, in the manpower and requirements office, working for a Wing Commander. There was myself as a Squadron Leader, two Flight Lieutenants, a Warrant Officer and a Corporal who all shared an office and we just got on with whatever came through the door.

It was a time of great upheaval for the Air Force – they were going through a process called ‘leaning’ which people will tell you is nothing about getting rid of people. That’s leaning as in slicing away layers of fat! We ended up having to do a lot more with if not fewer, certainly the same number of people. We had to send airmen to go and fill in for a shortage of air traffic control assistants. The army had a programme called LEAPP which was their version of the air picture over land. They were trying to reinvent the wheel and put the spokes on the outside and I said to them, ‘We’ve already been doing this for 50 years. We know what we are doing. Why don’t you just adapt what we do?’ I managed to find five or six jobs I could get rid of so that I could push the light blue, the RAF manpower, into the army LEAPP programme to give them at least a semblance of normality and common sense.

I worked for the late Group Captain Jane Millington, who is sadly now dead. She was an Oxbridge character with a brain the size of a planet. She got promoted to Air Commodore and I had weekly teleconferences with her.

It was a good time. We were all of a like mind, let’s just muck in and get this done. We’d all rally round – who’s got the good ideas about this? Then in 2007 I was promoted to Wing Commander and sent to Iraq as the AOC’s liaison officer and I hadn’t got a clue what that was. I flew out to Iraq which was all a bit of a culture shock.

Iraq

You go out there. You’re issued with all the kit you need. You’ve got a rifle, you’ve got a 9mm pistol, you go through the airport security just as when you go to Spain on your holiday, they have a look at all your luggage and everything. I’d got a rifle in one hand and a pistol in the other hand and they wouldn’t let me take my Leatherman pocket knife on the aeroplane! It was a civilian plane chartered by the Air Force to fly people out to Basra in a battered old 747. As we boarded I got the good news that I was responsible for everybody else on this aeroplane, as I was the senior officer. Luckily enough nothing happened, and we ended up in a place called Al Udeid in Quatar. Then we flew in a C130 to Basra, which is about two and a half hours up the Gulf, did a tactical descent into Basra airfield because there were genuine threats of manned portable air defence systems, so we came spiralling down from about 15,000 feet with no lights on, crashed onto the runway at Basra. This was to be my life for the next four months! I worked for Air Cdre Mike Harwood, the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) the RAF in the Gulf, who was a one star air commodore who lived and worked at Al Udeid. My day to day working place was with the army in the headquarters in Basra airfield, Basra COB (Command Operation Base). There were Air Force people who worked for the Army and were part of the Army disciplinary system and had to toe the Army line. But as I worked directly for the AOC, I was not in the Army Chain of Command, and so I could go to places and ask questions that someone who’s in the Army system, including light blue, couldn’t ask.

The first time I went into the morning briefing Lieutenant Colonel, Willy Swinton. (Scots Guards and Tilda Swinton’s brother), walked in. He spotted me as a new face in the crowded room and invited me for tea that afternoon at Camp Charlie, which is a camp within a camp surrounded by barbed wire and live-armed guards. I pulled up in my old Land Rover. Whereupon a soldier disappeared off to park it and I was shown into this large tent where Willy Swinton was sitting at one end behind a desk the size of a football pitch, Scots Guards tartan stretched across it and a table in the middle of the room with the regimental silver on it laid for tea! I remember looking around and thinking ‘any minute now John Cleese is gonna pop out here’. A soldier came in with a white napkin and tea on a silver service, cucumber sandwiches. Just like the last days of the Raj.

I played along with this and then the air raid siren went off which meant rockets were being fired into the base from outside and you could hear them bursting – they did kill people so I was thinking when the air raid siren went off that we would at least get under the table, but Willy just sat there drinking his tea and eating his cucumber sandwiches like nothing was happening!

The Scots Guards at that time had Challenger tanks so I managed to get some of his soldiers to fly to Al Udeid and let them sit in – show them the Tornados. Some of the Tornado aircrew would then fly in to Basra on the nightly C130 flight and Willy would let them drive a Chieftain tank around and we had quite a good thing going. When the time came for that Tornado squadron to leave the theatre they came up with the idea to have one of their Tornados from Marham in Norfolk to fly past Willy’s ancestral home and take a proper reconnaissance photograph of Kimmerghame House, Willy Swinton’s family home, a Victorian Gothic castle in the borders of Scotland. They had the photo, a lovely colour print, blown up, framed, and gave it to him. Willy almost had tears in his eyes, and he walked to the picture which was about three feet by two feet `You see that turret with that balcony on there? That’s where my father sits in a rocking chair with a blanket over his knees firing at you chaps with his 12 bore as you go past.’ [Laughs]. All mad as a box of frogs but lovely people. You know – somehow I believed him too!

Basra was really weird – we were being shot at on a daily basis and the safest place in the camp was in what they call your Baghdad coffin. We lived in ISO containers – the things you see on the back of lorries. I was a senior officer so I had my own. There was a camp bed and around it they built a wall with a little hole at the end, put sandbags around that and a layer of armour plate with sandbags on it. If any rockets came in that was the safest place to be.

Kevin Hahn, who had been my boss in my last job in the UK came out to do a job in Basra while I was there. He’d had his weekly washing done by the Indian company that did the catering. He’d hung it up in his ISO container to dry, gone off to work and came back to find that his clothes that he’d left hanging up were shredded and there was a big hole in the side of his container. He’d have been a goner.

Every Monday night I had to fly down to Al Udeid to brief the one star at his morning brief on a Tuesday morning. I wasn’t sure if I should be telling him what the army are doing! Should I be telling what I think they should be doing? I decided to do so, warts and all.

He was a workaholic, and I was a bit wary of him because he worked 18 hours a day He liked all the i’s dotted and the t’s crossed. When I was due to come home, I had to produce an end of tour report which was my thoughts and views on the four months that I’d done on how things are going, how we could do better, what we’re doing badly and all the rest of it. When I went to see him for my penultimate briefing I said to him, ‘This will be the world through the eyes of Wilks. Or I can write you just a bland report that said yes it was fine we came, we saw, we didn’t conquer, you know, we’ll carry on doing the same.’ He said, `No, it’s fine. You write the good stuff and give it to me.’ He agreed that it would remain with him. I wrote a 13 or 14 page report. Marked it up as secret, sent it off to him and went for my farewell interview with him. He said it was a thorough and detailed report.

High Wycombe

In March 2008 I went back as a Wing Commander to High Wycombe to do what they call a DC job . After two weeks I got sent to Cranwell to see an Air Commodore who had a one-star army Brigadier with him. On his desk was my report which had gone all the way up to the Chief of the Air Staff. So, despite Mike Harwood’s promises, the report had gone all the way up to the top of the Air Force.

I went back to do the job in High Wycombe where I was one of five wing commanders who were there 24/7/365 using the QRA aircraft, trying to make sure that a 9/11 never happened in the UK. I’d been out in Saudi Arabia when 9/11 happened, working with the Americans, and that was an eye opener that was quite frightening. The reaction of the Americans was unbelievable. ‘We’re gonna make Afghanistan into a car park you can see from the moon!’

That job was 95% boredom 5% hair’s on fire! You were guaranteed access to all sorts of people just by picking up a phone to a designated member of the cabinet – you’re talking Gordon Brown, Jack Straw, Miliband etc. I’d get briefings every morning from other organisations – people with letters and numbers before their name. We did one exercise which didn’t stop at the end of the exercise. Special Branch appeared mob-handed, impounded everything and interviewed everybody. As I was the boss who’d been running it, I was taken away into an office and interviewed for two hours. ‘Why did you say this? Why did you do that? What time did you do that? Why did you do it that way?’ You really felt like you were being hung out to dry. It wasn’t until the end of it that everybody suddenly relaxed over a cup of coffee and said they do it that way to make sure you are prepared and protected in that everything you said or did is covered one way or another.

Stavanger

I got out of there in August 2009 and went for a bit of a sinecure as my last tour of duty to the joint warfare centre in Stavanger, Norway.

That was exciting and frustrating in equal measure. Frustrating I suppose because I thought I knew better than the people that were already the way we should be doing it. Exciting because we ran big exercises involving hundreds of people flying into Norway. It was an umbrella organisation made up of various component parts and they had to do well enough on the exercise for the boss of the joint warfare to sign off that they were fit to be the NATO readiness force for the next six months.

But I got frustrated because the exercise had been running for a number of years and it no longer challenged people. After I’d been there a year, as a Wing Commander I was made the Officer of Prime Responsibility for building one of these big Steadfast exercises.

It was all about preparing people to go into an environment where they are essentially running a peace support operation, and therefore the ultimate sanction rests with the host nation. For example, if they had to go into Yemen to run an operation it would be the Yemenis who would tell them where they were going to be based, what they could do, where they could do it and when they could do it. We had got this NATO mentality of coming in to sort the problem out and just assuming that the Host Nation would acquiesce. This time I really wanted to work into this exercise some tank traps for these people. I wanted to give certainly the air component some really difficult problems to solve.

We did it and it cost a bit more money. We used role players, actors from the UN or from the Red Cross to play parts for these people to bounce off. We got them in a barracks 15 miles away and hired two cars for them so if they wanted to come and talk to somebody they had to ring up, make an appointment, make sure they could be there at the right time, get in the car and all the rest of it and so we changed the mindset a little bit . But it took me two years to get the wheels to move. It was a NATO organisation and a lot of nations don’t send their best people to NATO! People can be there, getting paid extra money, living in Norway and doing the minimum amount of work and sightseeing. They didn’t want to rock the boat because it might mean extra work for them. But we moved it forward and changed it. I went back subsequently as a contractor and was gratified to see that they were still tweaking it and moving on.

Retirement – then to NCIA in Brussels

I came home and left the Air Force in August 2012. Retired. Did nothing for 12 months, got bored. Someone said, ‘there’s a job at NCIA (NATO Communications and Information Agency) in Brussels – do you fancy it?’

I had to form my own company as I was going out there as a consultant. I worked there for three years and then the people I’d worked for moved from Brussels to The Hague. Six months later I went back to the Hague and stayed there until COVID hit. I worked from home for part of COVID and then when Ukraine started, the programme I was working on was put on the shelf. Ukraine is still going on and I’ve been retired two years now!

As a man in a suit I could say things that if I’d been in a uniform I couldn’t ever say. You could discuss with a Colonel why a plan was barking mad, and he had to take into account my 34 years of experience. I was working on ballistic missile defence, which was run primarily by Germans, Americans and Dutch and I got frustrated with them. Since we got rid of Bloodhound the RAF doesn’t have any missile defence. In the German and Dutch Airforce you could join the missile branch and go all the way up to the top of the tree not knowing anything else about the bigger picture of air command and control. After a particularly frustrating meeting at Ramstein in Germany I clearly remember saying: ‘In the Royal Air Force before anyone is allowed near Ground to Air Missiles we’d have had to fail at least two of those courses. Is it the same in your organisations?’ [Laughs] I was trying to say in a jocular way that there is much more to air defence and air command and control than missile defence. As I could get away with saying that I became an attack dog – there were too many people who wouldn’t say what needed to be said and far too often programmes went off in the wrong direction. I was kind of the ‘operational’ conscience in an engineering empire.

I didn’t find the transition to being a civilian too difficult. For the first four or five months I was out in the garden every day but when winter came along I got bored. I quickly got back into work and I slid into it because it was just like putting on a coat that I’d already been wearing for a long time and I knew what was in the pockets, The suit I was wearing wasn’t a blue one, and oftentimes it’d be a pair of corduroys and a shirt. The biggest transition was when I had to stop working because of Ukraine and COVID. I’m 67 now and I sometimes think I need to go and get a job and stack shelves in Tesco or something, give the money to charity. I could get a volunteer job, of course.

What the training and mindset of the RAF means

When you leave the Air Force, or the armed forces, you think you have no transferable skills. But there are a lot of transferable skills in what I prefer to call leadership, not management. Management is a thing that civilians do, and leadership should be a thing that military people do. For me leadership is taking people to places they would not necessarily want to go to do jobs they wouldn’t necessarily want to do and bringing them home safely again. You subconsciously learn skills and you know what you can do.

When a guy I used to work with left the Air Force he very successfully became the manager of a GP practice, although he had not gained the rank I had. The job that we did in the Air Force, in the fighter control branch, was to get the right thing in the right place at the right time to have the right effect – in civilian life I guess you could call that logistics. Being responsible for all the people working in a GP surgery is like being responsible for a flight of airmen in the Air Force. It’s getting the people to do things successfully, making them feel like it’s a job well done and fostering an esprit de corps. In the Air Force, I’d always get all the people that I was responsible for in one place at the very beginning and set out my standards. ‘This is what you can expect of me. You are responsible to me so if anyone outside the chain of command, even if it’s the station commander, comes directly to you and gives you a hard time I’ll tell him to talk to me, and pass the message down the chain. The other side of that coin is if I need you to work till nine o’clock tonight, you stay and you work until nine o’clock and you do your best. If next Wednesday I can let you go at three o’clock you’ll go home at three o’clock. I know that over the course of the year you’re working more than the average.’

‘The other thing is, never lie to me. If something goes wrong because you tried to do the right thing I will support you 100% no matter who comes after you. If it’s because you’ve been an idiot, I’ll still support you, but you’d better learn the lesson because you get one strike with me and then you’re out’. Give people the time, space and confidence to grow and do their job in the knowledge that they can do their best and if they muck it up, they’ve got someone who will put their arm around them and say, ‘That’s fine. Don’t do it like that again.’

In the way civilian life works, we don’t have people who empower people all the way down to the bottom of the chain. In a decentralised control you say go away and do it. If you can’t do it come back to me and tell me, but other than that, go away and do it, and I’ll judge you on how well you do it. I think in some way that’s how Parliament works. I wouldn’t pay any of the 650 of them in washers apart from two people: Penny Mordaunt and Ben Wallis. Penny Mordaunt was a Royal Navy officer, Ben Wallis was a Scots Guards officer, and they understand words like service, loyalty, accountability and respect. Too many people in positions of responsibility think you just get respect, you don’t have to earn it. And that loyalty is only a one-way street. They forget you have got to be loyal to those under you. You learn those things in the armed forces subconsciously.

If I had to choose one highlight of my career, it was being a Master Controller at Neatishead. Running the operation train set for a defence of the UK against airborne threat. That was again 90% just watching the world go by, 5% getting very interested in something and 5% of ‘oh my God my hair is on fire, what am I gonna to do now’? And making it up as you go along.

Andrew Wilkins (b. 1956) talking to WISEArchive on 27th March 2024 by Zoom from Northumberland. © 2024 WISEArchive. All Rights Reserved.