Steve joined the RAF in 1979 and had a successful and exciting career as a navigator, which involved connections with Neatishead Radar Station. After leaving the RAF he had a second successful career, this time in management consultancy.

Joining the RAF and attaining my dream of flying Phantoms

I knew at a young age that I wanted to fly. I was one of those who was absolutely enthused by Air Force jets, and I set my heart on it. I was very fortunate that when I applied at age 18 I was accepted as a direct entrant, so I skipped university. I was lucky enough to go through my training very swiftly and ended up flying what I considered to be the absolute premier aeroplane type that the Air Force had at that stage: the Phantom. When the RAF first took delivery of them, we flew them in the air to ground and reconnaissance roles but when the Jaguar came into service in 1976, the Phantom swapped to the air defence/air-to-air role, armed with missiles and gun. It was in that role that I spent my operational flying career.

Initially the RAF had two marks of Phantom: the FG1 (Fighter, Ground Attack, Mark 1), which was based at Leuchars in Fife, Scotland and the FGR2 (Fighter, Ground Attack, Reconnaissance) version, which was based at Coningsby in Lincolnshire, Wattisham in Suffolk and Wildenrath in Germany. Immediately after the Falklands War, a squadron’s worth of FGR2s went to the Falklands to defend the islands, so we procured a squadron’s worth of F-4Js from the US, which became 74 Squadron at Wattisham. It was a short-term purchase to fill the gap and meet our commitments to NATO.

I flew for a period of 13 years and then did a couple of staff ground tours at HQ 11 Group and at Strike Command before I decided to leave.

I managed 2000+ hours on the Phantom and the red and silver patch you can wear on your flight suit is one of the most striking in my opinion.

Unfortunately, the Phantom was a victim of the Options for Change in the early 1990s. Immediately after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 there was a political appetite for a ‘Peace Dividend’. Across the whole MOD estate, the search for savings started and the most significant cost reduction in an air environment at that time was to take one complete type of aircraft out of service because of all the supply chain that goes with it; unfortunately the Phantom was first on the chopping block. The end came very quickly. However, what it did mean is that towards the very end we had a very experienced force. On both 56 and 74 Squadrons, on which I served in ’91-92, there were few aircrew that had less than 1000 hours on type. It meant we had a very small training burden. The normal 3-year rotation of aircrew and the associated dilution and training burden didn’t exist.

Early training

When I joined the RAF, I undertook initial officer training at the Officer Cadet Training Unit which was based at RAF Henlow at that stage. It was a little over four months of basic officer training. From there you then go into your professional training, wherever that might be. For me as a navigator that meant RAF Finningley near Doncaster for both basic and advanced navigator training. At that time – ’79-’80 in addition to the ‘fast jets’ (Phantom & Buccaneer) we still had Victor, Vulcan and Shackleton squadrons and initial navigator training at that stage was still focussed a good deal towards those types. This initial basic training was undertaken in a Dominie (an HS125 business jet) where you primarily sat facing backwards. The crew would comprise two student navigators, an instructor navigator and a pilot. Sorties were circa three hours long navigating by taking ‘3 point fixes’ from various navigation aids and by star shots using sextants! For half of the sorties, you are ‘Second Nav’ and sit on the flight deck in what would otherwise be the co-pilot seat and do visual navigation validation exercises. At the end of the basic phase, you are streamed to either fast jet or multi-engine. If you’ve been streamed into the ‘Fast Jets’ world (Phantoms or Buccaneers two-seater aircraft), you then go on to the Jet Provost squadron where you’re now sitting facing forward on an ejection seat and doing visual navigation using map and stopwatch techniques followed by some basic intercept work – known as ‘rat and terriers’ – where one of the aircraft would fly a route and the other would endeavour to ‘bounce’ it.

These were huge fun and were fundamentally a game of hide and seek where the bounce’s objective is to try to get into missile or gun parameters without the other one seeing or knowing where you are. It calls for low-down cunning, use of the weather and the terrain, and working out where you think the other aircraft is likely to be. So for someone that’s going into the air defence world and is going to be flying a Phantom, it’s a brilliant introduction into thinking in three dimensions at that stage. Much later in training when you use the Phantom’s radar, you’ve already started to picture the air environment in its three dimensions.

While I was in training at Finningley there had sadly been a fatal Buccaneer accident while on Exercise Red Flag at Nellis Air Force Base near Las Vegas. Fatigue cracks in the wings were subsequently discovered that meant the Buccaneer fleet was grounded while the issue was resolved. For me, it meant competition was even harder for my beloved Phantom. I was very fortunate to be selected.

Conversion to the Phantom

The next step towards the front line was a six-month operational conversion course on the Phantom. That was done at the Phantom Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) at Coningsby. It started with three or four weeks of ground school and some simulator training. We had a thing called an AI trainer – an Air Intercept trainer – which was a facsimile of the Phantom radar in a classroom where you could start to get used to radar geometry. Most radars typically display a fan shape as they sweep from side to side. However, for intercepts, the Phantom display was square (known as a B scope). It meant that you could more easily see angles relative to you. But it was pretty mind blowing initially and took a while to get used to (I can still recall the headaches!) However, once you get your head around the concept it’s brilliant. The radar’s elevation was adjusted by a thumb wheel under your right thumb on a hand controller. Where modern fighters can automatically work out and display another aircraft’s geometry, our intercepts were done through three-dimensional mental gymnastics in the back seat. When you’re first learning it’s a bit like patting your head and rubbing your tummy at the same time; pretty hard to get your head around to start with. And then of course you progress and get accustomed to it and it becomes second nature.

I still recall my first trip in a Phantom on the OCU. Until then of course I’d been flying much smaller aircraft and suddenly you come and stand next to this huge 58-foot beast that you must climb up a ladder to get in and you think ‘Holy [insert expletive]’. As a student navigator you get a very experienced staff pilot for your first trip whose task is to show off the aircraft’s awesome capabilities. And he sure did so: he put it on the runway threshold, held it on the brakes, wound up to full power where you can feel and hear the aircraft champing at the bit to be released. Then he rocked the throttles outboard and engaged the afterburners, released the brakes and the acceleration kicked me in the back and threw my head back against the seat. The jet leaped off the runway and then he stood it on its tail and up we went vertically – wow, what a machine ….. what a fantastic machine!

As a Phantom navigator on the front-line during the Cold War

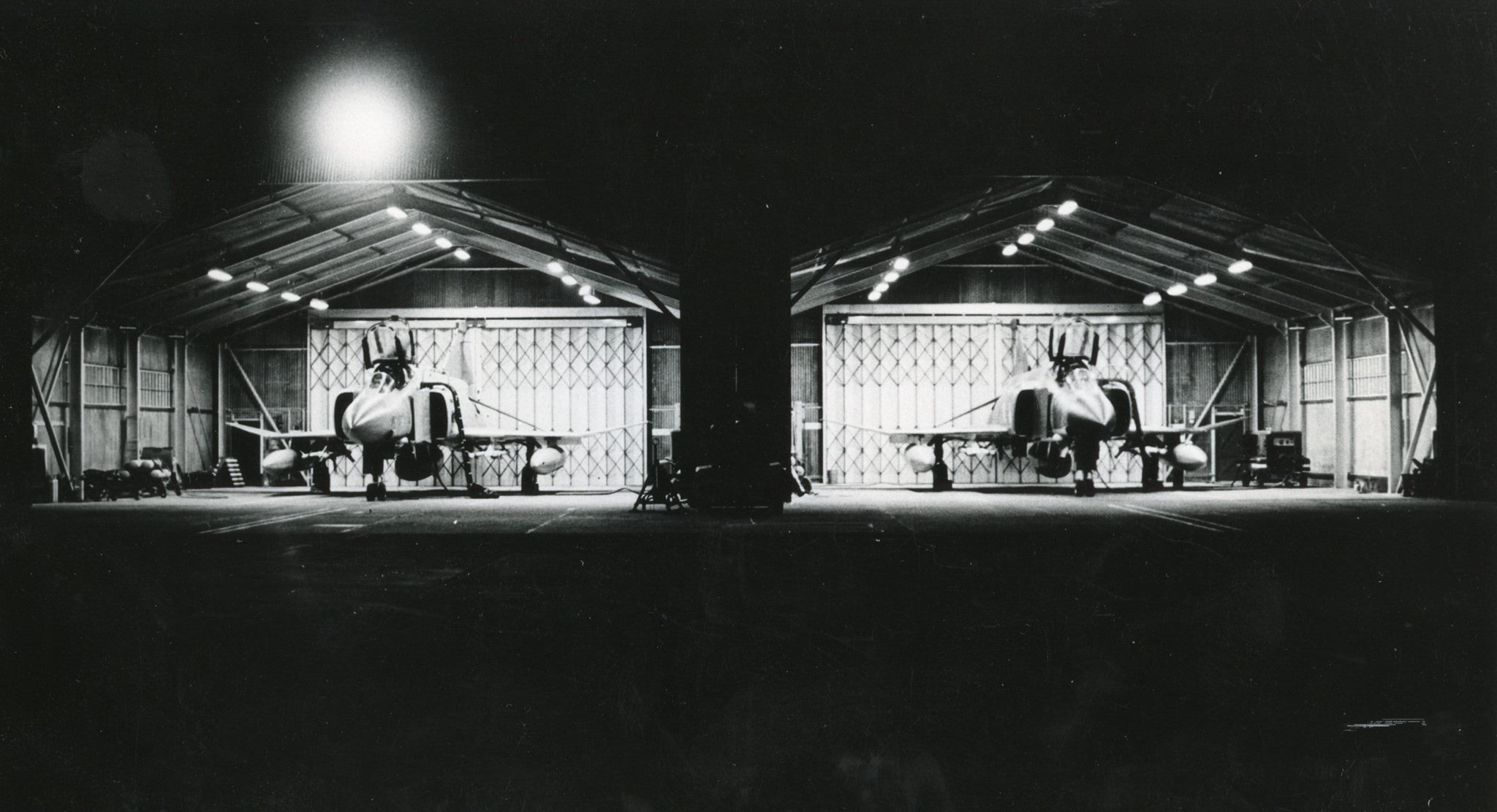

After I completed the Phantom OCU I was posted to Treble One (111) Squadron (‘Tremblers’) at Leuchars just outside St Andrews. MOD’s number one priority was, and still is, the defence of the homeland so within the UK we held fully armed aircraft on Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) readiness at all times. In my time, that meant two Phantoms at Leuchars on Northern QRA, each configured with eight live missiles and three external fuel tanks for maximum endurance. The same would be repeated in the southern part of the UK (Southern QRA) where the task would be shared between the Wattisham wing, 29 Squadron at Coningsby and the Lightnings at Binbrook.

This was a period when Soviet long-range aircraft would routinely probe our defence network. In addition to the UK landmass and our territorial waters, we had responsibility to NATO to police the international air space referred to as the UK Air Defence Region (UKADR). Our radar network would monitor that air space and our early warning collaboration with the other NATO nations would notify us if there were aircraft coming towards our area of responsibility. Quite a lot of the Soviet aircraft that came into the UKADR came from Murmansk, round the north of Norway, down the Norwegian Sea and either went through the Iceland Faroes Gap – sometimes these were transiting to Cuba and doing some intelligence gathering as they went – or they would come down and practice their missions against UK. QRA would be scrambled to intercept and shadow the intruders.

QRA duty was typically for a 24-hour period. We would come in around 8 o’clock in the morning, check over the aircraft, sign for it and formally take over responsibility from the off-going crew. Each of us would lay out our personal equipment in a manner that we each found fastest to get into. For me, that meant leaving my life jacket in an ‘open’ position at the bottom of the ladder and my bonedome (flying helmet) would be resting upside down on top of the engine intake ready for a swift rotation onto my forehead. Each of us would find our own level of ‘dressedness’ and comfort relative to the need to be airborne quickly. One of the biggest factors was our immersion suits which had rubber seals around the neck and wrists so that if you ever had to eject into the cold water it would provide you with some protection. But they were pretty uncomfortable to wear for a 24-hour period, especially given your feet were sealed inside your flying boots!

In this period of the Cold War it was very common for us to be scrambled to intercept these Soviet aircraft to let them know that we know they’re there and to see what they were up to. Sometimes there could be quite a few of them in our area at the same time requiring quite a few Phantoms to be out shadowing them. Some of them were quite friendly – they would hold up magazines and coke cans and smile. Others less so and would do their darndest to make life difficult. How friendly they were also depended on the type of aircraft and associated mission type; some types tended to be much more strait-laced and less friendly.

I was very fortunate in that I intercepted quite a variety of different types in my time, including one that we thought had been mothballed and had gone out of service some time ago. We carried a ‘Noddy’ reconnaissance guide with us and I remember on that particular occasion going through it three or four times. The thought pattern went something like: ‘Right so it’s got propellor engines so it’s definitely a Bear. It hasn’t got those lumps under there, so it isn’t one of those and it isn’t one of these so that means it has to be a – oh, it hasn’t got, ah’. So, I’d go back again and go through that process a couple of times until the eureka moment: ‘Ah, it’s one of those. Hmm, we haven’t seen one of those in a long time.’

In Germany we also held QRA duties and here it was called Battle Flight. The one big difference here from a comfort point of view was that we didn’t need to wear the immersion suit because we were operating over the land.

There is nothing more adrenalin pumping than the moment the box starts to squawk with an instruction. And sometimes it would be a ‘no notice’ – you’d simply get a ‘Scramble, scramble, scramble’ instruction. Other times you’d get brought to ‘Cockpit Readiness’ where you quickly strap in but keep the engines off and await further instructions. So throughout that whole Cold War period there was a very strong feeling of ‘there’s a job of work to do here’.

As I said, I was fortunate to intercept different types. Not only did I have live scrambles and intercepts while on Northern QRA and Southern QRA in the UK, but also from Battle Flight in Germany, in the Falkland Islands and while on detachment in Cyprus in the Mediterranean.

In the 80s the UK Air Defence Network was organised into three Sector Operations Centres (SOCs) of which Neatishead was one, looking after the southern half of the UK. In the north was Buchan and in between was Boulmer. They were in essence the top-level operational control units who had the overall big picture – the battle management environment. They would be the ones who were liaising with the other nations: the Norwegians, the Belgians, the Danes, the French and the Dutch and the like.

Alongside them were the control centres housing the Fighter Controllers with whom we would communicate while on task and who gave us directions towards our targets.

So on my first tour at Leuchars it was Buchan that I primarily operated with. When I subsequently went to Wattisham and served on 56(F) and 74(F) Squadrons, Neatishead was our typical controlling body. We’d work with them on our day-to-day training missions and when we were holding QRA.

An exciting morning

It was in 1989 while holding Southern QRA with Neatishead that I had one of my most exciting scrambles …

It was 4th July 1989, and we (56(F) Squadron) were mid-way through our three-week stint as providers of Southern QRA. The day had started very early – just before 4 am – when the station was subjected to a no-notice NATO TACEVAL (Tactical Evaluation).

Typically, these would involve NATO evaluators descending on the base – commonly at the most ungodly hours of two or three in the morning – setting off the station hooter and starting the stopwatch to assess our ability to generate all the aircraft with their full missile and gun war load, and crew them with ‘combat ready’ crews within a given timeframe. The first task was clearly to get everyone on base from wherever they lived and in these pre-mobile phone days, we used a cascade system to alert everyone.

One of my roles on the squadron at that time was to be what we called the ‘Warlord’ – the person who manages the squadron’s activities in a conflict or exercise environment. I would typically go straight to the Ops Room with my engineering counterparts and would be running the operations, making sure I’d got everything to brief the crews on, allocating the crews to aircraft, checking capabilities, readiness and the like, authorising them and getting them out to their armed aircraft. On some occasions, the NATO directing staff would select an armed aircraft and its crew and send it over to the air-to-air missile range on the west coast, to fire a live missile as a method to check that the missiles do work, that they’d been loaded correctly and that the end-to-end weapons system functioned properly.

On this particular day, I was already scheduled to be on QRA as Q1 so when I got to the Ops Room, I had a quick discussion with the boss, and we agreed that someone else would be Warlord and I’d continue to be Q1. So, I gathered my kit and with my Q1 pilot and Q2 colleagues we set off for the QRA shed to take over significantly earlier than the normal 8am.

After doing the handover/takeover we merrily settled in with tea and toast knowing that the rest of the base is a hive of activity getting all the other aircraft generated when out of the blue comes a message from Neatishead: ‘QRA to cockpit readiness’. We ran from the crew room, hitting the buzzer on the wall which opens the doors and sounds the klaxons as we went. Our ground crew came running out at high speed and started pulling caps off missiles and pins out of the aeroplane to ready it for launch as we strap in quickly and declare ourselves at Cockpit Readiness to Neatishead. On that day I was crewed with Mark Billingham, who very sadly passed away from cancer a few years ago aged just 54.

And then comes the instruction: ‘Q1 (I can’t remember what our call sign was at the time) Scramble, scramble, scramble. Vector 180. Climb to Angels 15. Buster’ – shorthand for climb to 15,000 feet, head south and fly as fast as you can without going supersonic! Turning south out of Wattisham was generally a no-no because not too far to the south is the start of controlled civilian airspace and the Heathrow holding pattern is not far beyond that. Something unusual is afoot, we thought!

As we race off everybody’s thinking this is part of the TACEVAL evaluation; we’re clearly being sent to go and fire a missile. That’s what we thought at that stage too. Wrong! So, we get airborne and leave the Wattisham air traffic frequency and straight onto the Neatishead frequency and we had a series of challenge and response authentications to ensure that we are talking to who we think we are. Once authenticated, the controller confirmed ‘Continue heading 180, maintain Angels 15 and Buster, we are moving Heathrow traffic out of the way’. Our adrenalin was now in overdrive as I acknowledged the instructions. Then came the follow-up transmission: ‘There is a Soviet Mig that is airborne over mainland Europe and heading west. It’s pilotless. If it crosses the mainland European coast you are to engage’. Instructions like that are pretty rare (understatement!) and need to be authenticated; he gave us the correct response that says this is a legitimate message that’s come from on high. Yee ha we thought!

We raced to overhead Dover, and, as instructed set up an east/west racetrack CAP (Combat Air Patrol), listening to a countdown of where this thing is. We made all the armament switches and double checked them so that we were ready to engage, then joked about how we were going to explain to the boss why it had taken all eight missiles to down a pilotless, non-deviating aircraft!

A couple of minutes later came the news that its flightpath had changed and was no longer heading towards UK. We were tasked to stay a little longer just in case it changed course before being released to head back to base.

It was only once we landed back afterwards that we heard that it had crashed in Belgium and had unfortunately impacted on a farmhouse killing a 19-year-old chap. We learned that it was a Russian Flogger D, deployed into what was then East Germany who had had an engine problem on take-off, and whose pilot had concluded that as it wasn’t accelerating, he should eject. It seems that the action of him ejecting cleared the engine problem and the aircraft then steadily climbed up to 30 odd thousand feet and went in a straight line until it ran out of fuel and crashed.

A unique experience; just a shame we didn’t actually get to squeeze the trigger and bring it down …..

My later RAF career

After that 1989 incident I saw the Phantom out of service in the autumn of 1992. In between, I went to 92 (East India) Squadron at Wildenrath in Germany for a short period, came back on promotion to 56(F) Squadron at Wattisham and then at the very end saw out the last three months with 74(F) Squadron. After we retired the aircraft in October 1992, I went to Headquarters 11 Group at Bentley Priory where my job was to design, build and run the twice-a-year live flying exercises for the air defence community.

At that stage many of the flying exercises were still built around Cold War scenarios, but by then of course the RAF had been heavily involved in the first Gulf War and this type of ‘out of area’ environment was likely to be the new normal, so I proposed that I re-engineered the exercises to make them much more tactically orientated.

One of the big challenges for the fighter community exercises is to ensure there are enough targets to go after, to intercept and engage, and to enact the rules of engagement. It seemed to me that the secret was in making sure the ‘targets’ would get good training value from participating in the exercises. So, I went to all the ‘Mud Mover’ squadrons – the air-to-ground community, the Jaguar, Tornado and Harriers squadrons to find out what they’d need. I did the same in northern Europe with the Dutch, the Belgians, the Danes, the Norwegians, the Germans, the French and the USAF. When I asked ‘What do you guys need to make this really exciting for you?’ the response I got was ‘Big mixed aircraft packages, air-to-air refuelling realistic and juicy targets to attack, some with live bombs and some with just practice bombs and some synthetic.’

So we redesigned around that environment. We took scenarios that were old and tired and really transformed and modernised them to the extent where, after the very first one, we had lots of the other nations contacting us to say ‘Just tell us the dates of the next one. We’re in’. Instead of sending four aircraft to subsequent exercises, they sent eight or twelve or even sixteen so we knew we’d hit on the kind of quality training value that we needed.

At the end of that tour, I was selected to go to Advanced Staff College, which was a year-long Master’s level residential course. It was the last single service RAF one before they became Joint Service.

After that I went to Strike Command Plans Division responsible for the Air Defence environment. My small team had responsibility for the entry to service plans for what was EuroFighter at the time, now Typhoon, Sentinel, Tornado F3 and the UK Air Defence Ground Environment (Neatishead, Buchan, Saxa Vord and Staxton Wold etc).

In 1997 as part of the Strategic Defence Review I, together with a Royal Navy and an Army colleague, was tasked to be part of one of the workstreams related to the procurement of new equipment and getting the needs of the frontline operators of that equipment built in much earlier in the lifecycle. With an already busy job in the Plans Division this additional activity was stretching to say the least!

However, in addition to working with the Army and Navy colleagues and a couple of civil servants, I was also working with management consultants from McKinsey, KPMG and PWC. It led me to realise I had a suite of consulting skills that I didn’t know I had when I was in the cockpit, and I started to reflect on what I’d done in transforming all the exercise environments and what I’d been doing transforming the Air Defence environment while I was in Plans. It led me to the decision to turn down my next role (a Command flying job) and to leave the Service for a job in Management Consultancy.

My subsequent career in consultancy

I was very fortunate to be offered roles with both PWC and KPMG but these would have been in their public sector practices and I would have faced off to the MOD. I decided that if I was going to make this career change, I needed to be brave and make a complete break. So I joined a relatively small, 25-person management consultancy in London. My new colleagues had just done a diagnostic analysis for what was then the Derbyshire Building Society and my job was to work with the CEO to create and deliver the programme of work that would transform his business. I took my RAF uniform off on the Friday and on the Monday I was sitting in his office – just him and me – with all these jigsaw pieces on the table working out with him which things to do, how we will do it, in what order and to what benefit and impact.

When I look back I kind of smile and recall that my knowledge of building societies at that time could be written on the back of a stamp, in capital letters with a four-inch paint brush. For the next six or eight weeks I kept thinking someone’s going to come and tap me on the shoulder and say ‘Jolly good, well done, now get out’. But it didn’t happen!

I was asked about how I found the transition from Service to civilian life. I think the reality was that I was too busy and too focused and too determined to make it work to properly notice the transition. I don’t doubt that it was a huge cultural change. At the very basics I joined a brand new team. The four other people from the consultancy that I was working with had been with that organisation for a few years. They had done lots of this kind of work and I pitch up as the new boy on the block and as their boss, leading the assignment, responsible for the engagement, its success and the revenue that I’m now bringing into the Consultancy. So, my head was just so full that I don’t think I really had the opportunity to sit back and concern myself with the transition and, perhaps if I had, I might have said ‘Are you sure you know what you’re doing here, young man?’ But it worked out.

I’ve since worked with all sorts of clients in all sorts of environments and geographies in the 24 years that I’ve been doing this kind of work. I’ve been hugely fortunate in that I’ve never been pigeonholed into any one sector. I’ve worked with clients in the public, not-for-profit and private sectors. Some have been small with just a handful of people, through to those with 130,000 like Asda or 220,000 like the Government of Jamaica. Some have been FTSE100 clients like Imperial Tobacco and British Telecom; others have been small start-up businesses.

Highlights of my career

Trying to decide what has been the highlight of my career is a bit like deciding which is my favourite child. I think the only thing I can say is that I do genuinely believe that I have been very fortunate. And I don’t think it’s just lucky; I think the thing that I now recognise (in my more mature years) is that I’ve been pretty successful at identifying the opportunities as they come into view or when they cross my sightline so to speak. It enables me to think ‘that’s an opportunity I need to take up’.

I’m what might be called a self-starter and I’m curious about things. I know can get bored easily and I always want to ‘push the envelope’. If I look at my RAF career, while I was flying I always wanted to do the more difficult, more complex things. As an example in those last couple of years I used to run some week-long internal exercises in the squadron where I would call round all my exec friends in other squadrons and say ‘I’m looking to try to build an exercise for such and such a week. Do you want to come and play?’ And generally the answer was yes, because they knew what sort of quality event it would be! Internally, I’d make it even more challenging by, for example, running a 16 aircraft mission with no talk on the radio; completely silent!

Steve Lungley (b. 1960) talking to WISEArchive by Zoom from Warfield on 20th February 2024.

© 2024 WISEArchive. All Rights Reserved.