Jill talks about her 32 years’ service as a civilian volunteer at RAF Neatishead helping to warn and protect the civilian population in case of nuclear war.

Jill Ward talks about her 32 years’ service as a civilian volunteer at RAF Neatishead helping to warn and protect the civilian population in case of nuclear war.

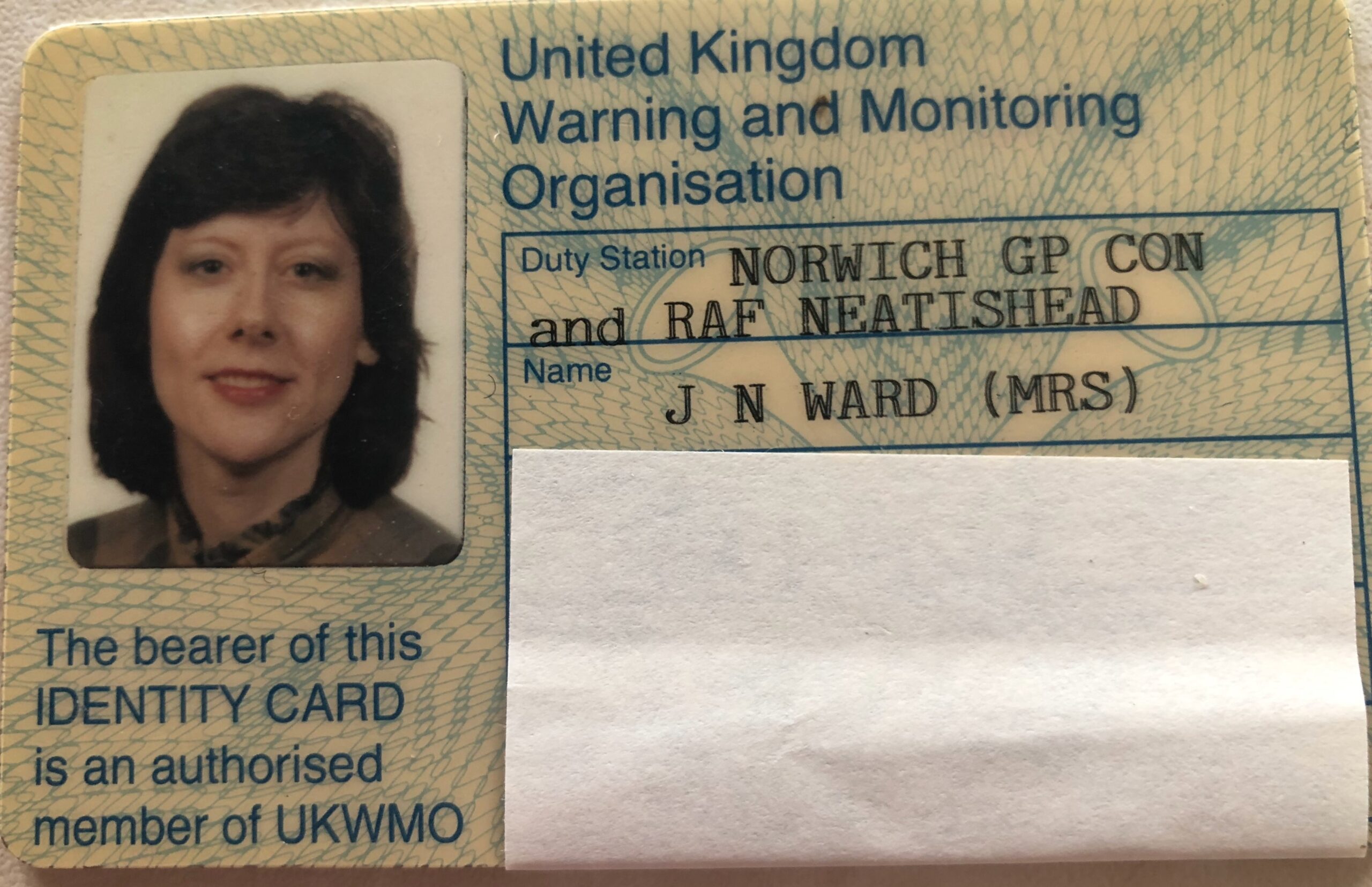

Joining the UK Warning and Monitoring Organisation (UKWNO)

I was working for Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO), and we were asked to place an advert in our weekly information circular on behalf of the Home Office to recruit volunteers for UKWMO. I had always wanted to join the Civil Defence but it had died out long before I was able to join. So, seeing the advert I thought it was an ideal opportunity. I was able to get myself considered and managed to go – but I don’t know whether they would have weeded me out if I hadn’t been dealing with the applications!

I was invited for interview where I was told you had to be over 22. I said, ‘What happens if you are under 22?’ The Chief Controller replied, ‘Well 21 and how many months?’ So, I went ‘One in two weeks’ time’. I was vastly underage as well as being a woman.

Then I got lots of letters saying my application was being considered. Many years later, I heard that, because I had been with HMSO which had computers, a fairly new thing in the early 1970s, they thought I was a scientist or something in computers.

They didn’t find out for some years that I was just admin. But because I was young and maybe because it was at the start of women joining such things, I was accepted. I believe there was just one other woman in the whole of the UKWMO outfit at the time – she had joined in Lincolnshire because her husband was a member.

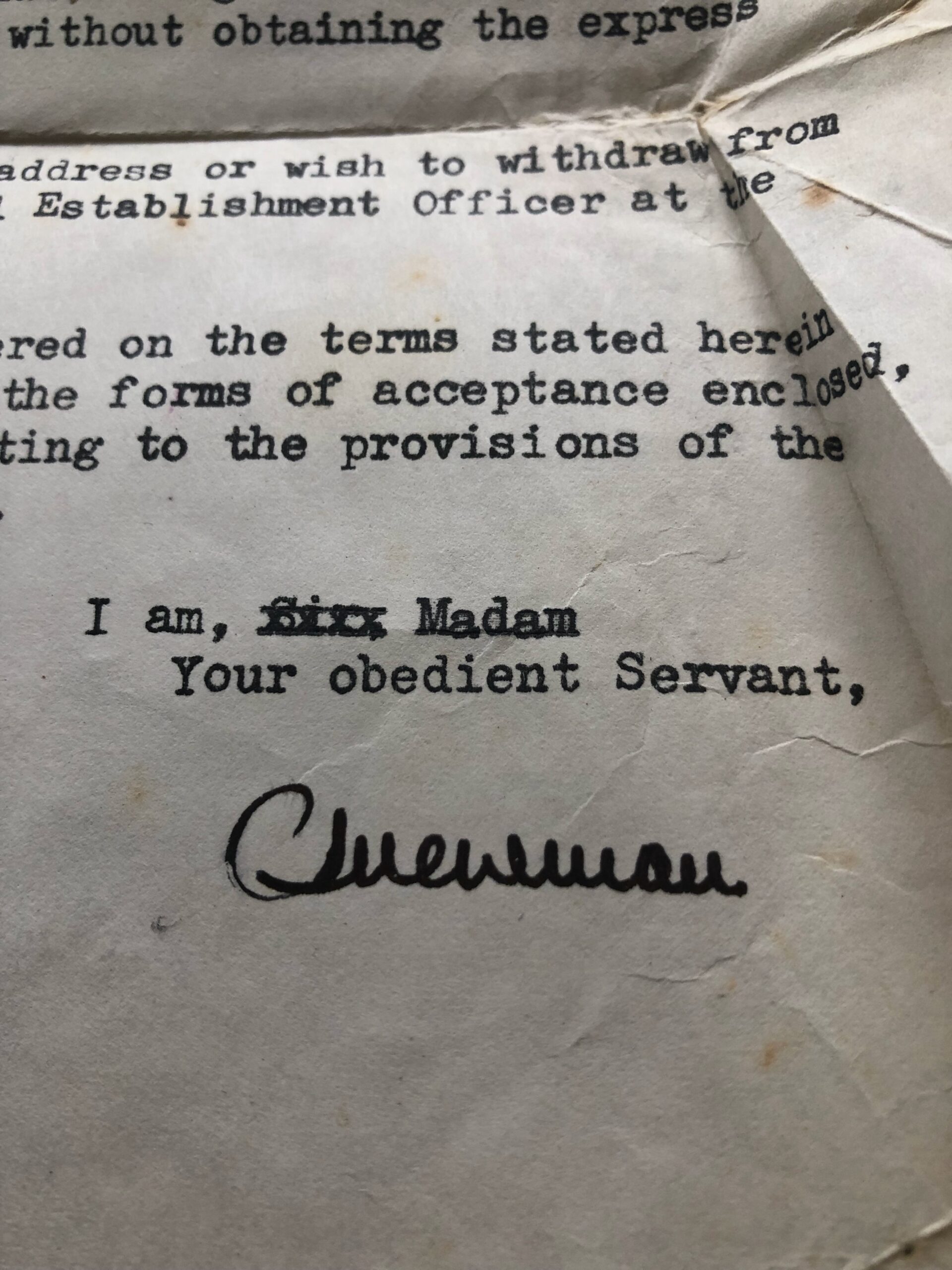

I applied in January 1972 and got taken on in April 1972 with the original letter addressed to ‘Dear Sir’, and ending, ‘I remain, Sir, your obedient Servant’. They had to type over this and put in ‘Dear Madam’. After that, the letters were addressed to me personally, so whether I changed things or whether it was due for a change in the Home Office, I don’t know – I like to think it was the latter.

I applied in January 1972 and got taken on in April 1972 with the original letter addressed to ‘Dear Sir’, and ending, ‘I remain, Sir, your obedient Servant’. They had to type over this and put in ‘Dear Madam’. After that, the letters were addressed to me personally, so whether I changed things or whether it was due for a change in the Home Office, I don’t know – I like to think it was the latter.

Joining was really interesting because going up, they were all men. Many had been in the RAF during the war so we had people with DFCs and DSOs and really amazing pilots. Most of the others had done National Service. I was female, I was too young, and it wasn’t my background, so it was slightly tricky in some ways. But if you decide you want to do it, you have to learn.However, I was incredibly shy and I did find it very overwhelming with lots of men. But they were all really nice to me, not patronizing or nasty to me in any way. I didn’t realise at the time but, latterly, I understood that they would accompany me into areas when they thought I might not be safe, and they accompanied me to my room when we were away at conferences to make sure I was safe from drunken men from different areas. I realise it was really sweet of them.

Volunteering with UKWMO

When I started, we used to do training two nights a month for two hours, 7.30 to 9 30 on the first and third Mondays of the month, and every now and then we had a weekend exercise and very occasionally a 24-hour exercise. This was co-training with the Royal Observer Corp (ROC) at Chartwell Road in Norwich. It was a bunker but now it’s been filled in and a Co-op built over the top.

Our role in UKMWO was dealing with data on nuclear explosions and forecasting the extent of fallout across the country in the event of a nuclear war. We worked with the ROC, although we were a civilian organisation working for the Home Office whereas they were a uniformed part of the Ministry of Defence. The ROC got information from posts all over the country and passed it to us, and our job was to send it on to the Home Office to warn them about bombs which had landed and the fallout area. People would then know where it was safe to go outside to perform tasks. Essentially our role was to protect the civilian population.

Some people might remember, ‘Protect and Survive’ which was sent to all households in the late 1960s or 1970s. It advised that in the event of a nuclear attack, you should find somewhere to go such as under the stairs. You put white tape over your windows to stop the glass falling in and you put your battery radio in a biscuit tin to stop the EMP (Electromagnetic Pulse) getting at it, so you could still hear what was going on. In retrospect, whether it would all have actually worked… I think you would have to be extremely lucky, but I guess it was better than nothing.

Our job in the bunker

When you went into the bunker there was a decontamination area, although I don’t know how we were to be decontaminated because I don’t think we ever practiced. And we had no equipment. I used to say, ‘ But, where are the body bags?’ People were going to die and we didn’t have body bags so, looking back, it was a bit of a game. But if you didn’t live through the Cold War, I don’t think you realise how frightening it was but we all lived in hope; fortunately, I don’t remember things like the Bay of Pigs or some of the really bad days. My brother used to say I was the only Eve amongst all those Adams. I always thought if there was war, I would get a really good haircut as I would be stuck in the bunker for months!

During exercises, information came in via the ROC and they would write it up backwards on transparent screens so we could read it frontward – we ended up learning a bit of backward mirror writing too. We could see where the bombs were falling and we monitored the decay rates (obviously all theoretically on logarithmic charts) so we could then see whether it was safe for people to go outside or why there was a sudden increase in fallout – perhaps because it was a sodium bomb – which meant it had landed in the sea as opposed to on the land.

We were in close liaison with attached neighbouring groups in Lincoln, Bedford and Colchester and all these ultimately reported to the Home Office which was based in Cowley in Oxford. In the event of a nuclear attack, they would have communicated with the BBC, because it was the BBC who had to send out the information to the general populace about going down the hole, and when it would be safe to come up again.

Our job was very much based on liaison and you have to remember that this was analogue days so there were no computers. The ROC got the information via a teleprinter but presumably there were also direct lines.

We had passes to allow us to get into the bunker – the original passes were to tell the police ‘to let us in unhindered’. You can imagine all the people trying to get down the bunker themselves for safety and the police were just going to let us in – I think not! But it was a matter of doing our bit. Of course, you can look back to fifty years ago with the benefit of hindsight but do we know what it’s going to be like fifty years into the future? You can’t guess, so you can only do what you can.

So, I did that for a number of years.

Transferring to RAF Neatishead

Volunteering in Norwich was purely with UKWMO and the ROC. Then about 1977 I was asked if I would volunteer to do some joint exercises at RAF Neatishead. I only lived five minutes away and thus, in the event of the twenty minutes to get down a bunker, I had a better chance of getting there than some of the others! So, I thought , why not?

Going to Neatishead was very different because I was used to a civilian outfit. There, it was obviously very military and in 1977 there were still a lot of RAF personnel working who knew what they were doing – the cuts came later. I was still part of the Home Office but we did less with the ROC. There was a group of ROC personnel based in R12 at Neatishead, but because there had been a fire in the lower bunker, we were based in a different building.

At Neatishead I went in by the main entrance and then went through security and showing authorisation letters, as they had to know why you were attending before you parked the car. You went into a building above ground where there was a small mess for officers. I don’t know where the other ranks went. There was the upper bridge and middle bridge – all darkened areas where you had to get your sight in. Those areas have now been converted for displays for the museum. Then there was the radar equipment itself, and an area for equipment behind the scenes.

When we first started, we worked above ground because in 1966 there had been a fire in the bunker. When it reopened things were completely different because we had to go down a whole group of stairs to go underground; there was a small mess there. Above ground, there was a place where the RAF Regiment was and we did our training there.

The Group Captain in charge of Neatishead would be on upper bridge where he could hear all that was going on. We worked on the middle bridge with half a dozen or so radar screens, and we learned to read the screens in dark conditions and also ‘RAF speak’, because we were listening in. The ground floor had all the quick reaction alerts, QRAs, which were linked to the different air force bases which sent out the fighters, because Neatishead could see when bombers were coming in from – presumably Russia, that was always the bête noire. I emphasise that this was all pre-digital because I think that was one of the reasons why everything was stood down and disbanded. Who was going to pay for it to be upgraded?

So, we were there on the middle bridge for many years, not knowing really what was happening. We attended exercises but we didn’t have deep or lengthy training. We had a special connection, a special jack and a special headset that got me directly to the Home Office. I later donated them to the museum after universal peace broke out.

I was part of the Home Office, but this was all voluntary, we weren’t paid. We did get our expenses so we got mileage to and from Neatishead and a subsistence allowance in line with civil service allowances. You could occasionally get a cup of tea but I don’t remember getting any food unless we were on a NATO exercise when we were allowed to join them at lunchtime. I have to say, the short crust pastry on the steak pie was really one of the best I have ever had! I did congratulate the chef and I don’t think he had ever been congratulated before – what is this weird woman doing!

So, this continued and gradually over the years, we did a little more training; I always felt that we had got better trained after the bunker was reopened. That’s when life became more formal; we got proper training and everybody was back where they were supposed to be.

UKWMO disbanded to become HOWLOs

Peace broke out in 1992 and the government decided to stand down the Royal Observer Corps. It was going to be their seventieth anniversary, and the Queen asked, ‘Do I congratulate them on surviving seventy years and on to the future or do I say good-bye?’ They decided good-bye.

This had a great impact on what we did in UKMWO because we got all our information via the ROC. So, it was decided to disband UKWMO and four of us became a specialized team based at Neatishead. I was chosen as leader and we became HOWLOs – Home Office Warning Liaison Officers.

There was another woman in the team who had been in the ROC and had done some work at Neatishead; another UKWMO person, and someone who had joined UKWMO from the ROC within the previous six months, so they all had a bit of an idea about Neatishead but not about the Home Office side. Now our connection was only with Neatishead, other than reporting back to the Home Office.

The four of us all got on and became friends. It is very sad to think that all are now dead. One died when she was very young and the latest one died in January this year. So, it is just me left to tell you these stories of HOWLOs and COWLOs.

When we became HOWLOs, we got more specific training. We were allocated a Flight Lieutenant as our liaison officer, some of whom were better than others – some didn’t contact us at all when exercises were going to happen or help us, while others were excellent. So, our training depended upon our liaison officer.

HOWLO Training

We started getting people who realised that, while we were civilians, we were very keen and we did our bit. Once a month on a Friday night, we would go for training after work, from about half seven to half nine or ten o’clock, and we started getting specific training on how to read radar screens, interpret things and know what they meant. Now I had never been particularly interested in bombers and interceptors… they were Russian, Tupolev’s, things like that. I never knew which were bombers and which were interceptors, so I used to come home and say to my husband, ‘What’s a Tupolev 121?’ And he would say, ‘Lancaster’. He tried to translate them into Lancasters and Spitfires for me which doesn’t sound very professional, but you just have to learn, you had to know bombers from interceptors. But I could never understand how my husband who wasn’t interested in any of this knew exactly what a Tupolev 121 or 157 was!

Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Kit

We had had localised exercises with UKWMO previously but now we got involved with NATO exercises. NATO representatives would come along and watch how Neatishead was reacting and how they were doing. One time, a NATO investigator came over for an exercise and he happened to be one of our previous liaison officers. In the middle of it, when we were looking to see when the bombers were coming in – our job being to warn the population that a bomb was on the way by passing that information onto the Home Office – a young aircraftsman came with open arms and said to me, ‘Here’s your NBC kit’.

Now I know my eyesight isn’t very good and we were in semi-darkness looking at the radar screens, but I couldn’t see anything between his arms and I didn’t know what was going on. Remember, I was just an innocent civilian and for these people this was their lifetime’s work. He kept saying, ‘Your kit, Ma’am’ and I had no idea what I was supposed to do. Fortunately, the Flight Lieutenant, our previous liaison officer, came over and said, ‘You should have been issued with kit so I asked where’s the kit for the HOWLOs?’ So, they had to pretend to get some out of store but they didn’t have anything for you. But they still had to go through all the sequencing!’

I was standing there thinking it was like the Emperor’s new clothes – there was nothing there and I didn’t know what I was supposed to say or do. I was really pleased when that particular Flight Lieutenant explained it to me. There were lots of times when I was embarrassed, but after that we did get better training.

The RAF all had NBC (Nuclear, Biological and Chemical) kit with gas masks and every now and again they would shout, ‘gas, gas, gas’ and everyone would put on gas masks. But we had no equipment whatsoever. This particular time, the Flight Lieutenant, who knew us, and felt that maybe our training should have gone on a bit longer and in more depth, said something to somebody…

We then had training with the RAF Regiment to learn how to put on the NBC kit – ‘on in five, stay alive, on in nine, just in time!’ Putting on the gas mask was difficult; all the RAF female personnel had their hair tied back but I didn’t, so I had to tie mine up. Then the four of us had to do the buddy checks.

We used to scribble notes and the Sergeant said, ‘I don’t understand this, you come along once a month or whatever, and take all these notes; I’ve people here whose work it is, and they are not half as interested as you’. We used to apologise to him for not understanding things and he liked that we were so engaged. ’

Fire training

We were also given fire training, which was particularly important at Neatishead because there had been a fire in the underground bunker which had forced its closure for about 15 years. It had burnt it out. The fire resulted in the loss of three or four firemen. I saw the bunker and the fingerprints in the smoke of the firemen who had died. The door handle was not where they would have expected it to be, and they were just inches away from opening the door to get out of the bunker. I think once you have seen that, the whole idea of health and safety processes that other people laugh at, makes sense. They were young men with families, and they died for no reason.

I was very keen that we did the training, which we did with the fire brigade. There was one funny incident when they were training us to use the hoses… I thought I would take this opportunity to wash my car which was within walking distance until the fireman said he wouldn’t advise it – the water was so powerful it would take the paint off as well as clean it. So, fortunately, no damage was done – I’d thought that it would be a free wash!

We got more and more involved and were in the loop with air marshals who directed the air traffic and set the interceptors up to intercept the incoming bombers. We were learning the lingo which was difficult, and passing on information.

From HOWLOs to COWLOs

So, we were the Home Office Warning and Liaison Officers dealing with civilian protection. There was our group in Neatishead and two others, one in Boulmer in Northumberland and the other in Buchan in Scotland – ultimately, they closed all of us down because universal peace broke out in 2002 and we weren’t needed.

I was in close liaison with the other groups, particularly with Boulmer. We used to meet up at the Home Office emergency planning department in Easingwold – where all Home Office civil defence training was carried out – and we were given extra training and background at Home Office conferences. However, again because the Home Office was shrinking and doing different things, about 2000 we became COWLOs, Cabinet Office Warning and Liaison Officers.

We were then an adjunct of the Cabinet Office which had no previous history of people like us, and it seemed to me that they were not interested either. Our Liaison Officer got us new binders and new information so we could read up on everything we had to learn. He then got pictures of cows and put them on the front page for us all, because we were COWLOs – there were heifers and bulls! Probably It all sounds trite, but it was a good way of working with each other. If you can have a laugh and a joke and still get the work done, that’s quite good.

Fitting in with the RAF as civilians

Some of the people we worked with there were just amazed that as civilians we put ourselves out, and learnt so much. I believe there was more equality in the RAF because it was a much more recent service. The Army could have generations of fathers and sons all being part of a particular regiment, which didn’t happen in the RAF.

We only had one female RAF liaison officer and she and I are still in contact thirty odd years later. She has travelled the world and says, come over and visit me. That was good because we could talk woman to woman, not the lingo that maybe the RAF used. But when younger personnel came in, they were more on our wavelength so that was interesting. As volunteers, learning about such things as bombs and sidewinder missiles and all about trajectories, that takes a bit of learning. I’m not saying we were experts but at least, we tried.

The RAF never really knew what to do with me. I went everywhere and for the longest time they didn’t know what to do with me because I was in civilian clothes when everybody else was in uniform. Sometimes an exercise would begin on a Monday, and we would arrive on the Friday because it was only the end of the exercise that affected us. Once I turned up when they said they weren’t expecting me and I was put under an armed escort. I don’t know whether there were bullets in the rifle, but this young aircraft man put me in the officers’ mess. Of course, I didn’t know who everyone was, and they certainly didn’t know who I was but he was there to guard me. He had to stand outside when I went to the loo, poor man, I felt very embarrassed for him!

Another time, when again we didn’t appreciate all the niceties of the RAF exercise we were on, my colleague and I were just walking across to our cars… We didn’t realise that the markers on the field were to show where bombs had supposedly gone off. Walking out was not a good idea because the station was being ‘bombed!’ And at that moment, planes came across and they were the lowest I had ever seen. They were flying over the station and pretending to bomb it. That was really scary. We didn’t know, because nobody had told us – it always depended on how well briefed we were.

Another time I went over to the station for an exercise, and as I was off to London in the afternoon for a course, I went in a skirt suit – we didn’t have a uniform. I had been asked if I wanted to go over to Neatishead as they were having a proper exercise and were having bombs dropped. I remember being there with one of my colleagues and speaking to someone from the German air force who spoke immaculate English while we were waiting for the Belgian air force to come over. What on earth must he have thought of me in my suit, on the edge of an airfield as the planes were coming over. But it was fascinating talking to the officer – it was just at the time when the RAF was coming out of Germany and the British Air Force of the Rhine were being shipped home. I said, ‘You must be really glad that we are finally leaving Germany but he said, ‘No, now is the time we all need to liaise, I’m really sorry you are leaving’. I couldn’t understand that.

Special leave for exercises

When I joined the HOWLO team, we had to sign the Official Secrets Act so I didn’t say much about my volunteering. At work, they knew I volunteered for UKWMO because I was allowed five days a year special leave to attend exercises. However, when I joined a new department, they were revising the terms and conditions book and I saw that I was no longer down for special leave. I rang the person renewing the regulations and asked what had happened to the leave for HOWLOs? He said he had contacted the Home Office and only 12 people were affected so had not included it. I said, ‘It just so happens that I am one of those 12’, so I was given a special dispensation. I don’t remember ever using up the five days except when I was on Home Office training courses at Moreton-in-Marsh at the very beginning; the others were just odd days when we were having NATO exercises.

Volunteering and learning about bombs and civilian protection was scary but it got better over time. And after the Berlin Wall came down and we had the détente and we felt safer. But it was still a scary time. My view was always, don’t worry about the Russians, I had been to Russia in 1968 and I had met Russians who had been in the war, and I felt that they wouldn’t start a nuclear attack although they were our main opponents. There were too many old men at that time who knew what war was like.

After I married, I was always scared what would happen in the case of war and I had to go down the bunker, because I wouldn’t be able to phone my husband. However, part of my day job involved selecting volunteers to go down another bunker just outside Norwich, so I volunteered him for that! He wasn’t very happy when I eventually told him. ‘That’s my decision to make’. But I said, ‘I want to know where you are and how I can get hold of you’. I thought I was doing the right thing, but …

The disbanding of COWLOs in 2004

In 2004, the Cabinet Office decided that we should be disbanded. Nobody knew what to do with us. I think the previous people who had been in charge in various government departments had all been involved in the second world war or Korea, and so were aware of protecting personnel. However, anybody in charge from ‘92 onwards had no idea, and with détente it wasn’t seen to be needed; money could be funnelled elsewhere. I do feel we tried to do our bit but I am just really grateful that we didn’t have to act on it.

I had been given the long service Defence Medal, and would have got a bar to it except by then we had moved over to the Cabinet Office which didn’t have the same rights to issue the bar. An order by the Privy Council was needed and they obviously didn’t think it was worth the expenditure. But I had my Medal and that was something to be proud of.

Socially, there wasn’t much contact between us and the RAF, however, towards the end I was invited to the sunset ceremony that they held each year, where helicopters and typhoons flew over.

My MBE Award

My thirty-two years of volunteering,1972 to 2004, did help towards my receiving the MBE the year afterwards from my civil service department. It was presented by the then Prince Charles, and was for work I had done towards Health and Safety. It was just before my husband died so it was nice to be presented and have that. But I think without the work I had done for the Home Office I wouldn’t have got it. It contributed towards you being considered a person who has done something for your country.

My thirty-two years of volunteering,1972 to 2004, did help towards my receiving the MBE the year afterwards from my civil service department. It was presented by the then Prince Charles, and was for work I had done towards Health and Safety. It was just before my husband died so it was nice to be presented and have that. But I think without the work I had done for the Home Office I wouldn’t have got it. It contributed towards you being considered a person who has done something for your country.

Jill Ward talking to WISEArchive on 21st September 2023 at Brundall. © 2024 WISEArchive. All Rights Reserved.